EUROPE at the Frontlines of UKRAINE-RUSSIA WAR

FROM YALTA TO CRIMEA: EUROPE’S CONFRONTATION WITH RUSSIAN BLOCKADES:

Yalta Agreement of February 1945 laid the groundwork for the division of Europe between East and West. While the partition allowed Moscow to install puppet governments in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania and elsewhere, western Europe aligned with the US and developed democratic systems.

Shortly after Yalta, the Soviet blockade of Berlin in June 1948 marked the most pivotal political events leading directly to the formation of NATO in 1949. The Soviets were concerned that West Berlin, a city located deep inside the Soviet controlled communist territory in Germany, with its capitalist and democratic system would become a propaganda tool to undermine Soviet system in Germany and beyond.

A war torn Europe without unified military forces could do little to resist an intimidating and victorious Soviet army, which had quickly tapped into additional manpower from Eastern European countries. Through the blockade of Berlin, Stalin’s primary aim was to block Western access to the heart of Germany. If the Western Allies did not respond with the airlifts, the Soviets might have pushed further west and set the stage to take over all of Germany.

Unlike what Stalin had hoped for, western alliance did not abandon West Berlin. Rather than risk losing entire Germany to the Soviets, and potentially facing regime changes at home, the West consolidated militarily under NATO. Within a month the Soviets ended the blockade.

Russian Annexations Of Crimea & Donbas: Geopolitical Chokehold on EU:

Much like the situation in Berlin at the start of Cold War, Russia’s annexations of Crimea in 2014 and parts of Donbas in 2022 have effectively served as de facto blockades against the EU. Prior to the annexations, the EU had been seriously considering the full integration of Ukraine into the Union. Brussels’s first major move in that direction was the proposed “EU Association Agreement (EUAA)”, scheduled to be signed in late 2013, which aimed to deepen Ukraine’s partnership with the EU.

Had Yanukovich not rejected the agreement under pressure from Moscow, the agreement would have allowed the EU to expand its influence across Ukraine, and to establish “Common Security and Defense Policy” missions, including counterterrorism and cybersecurity operations. EU’s push for EUAA may have accelerated the annexation of Crimea in a sense, as Kyiv government signed the agreement in March 2014, only three days before Putin signed annexation treaty with Crimean leaders.

Through the annexations, Russia secured key regions and effectively blocked the EU’s access to strategic resources. This also created a barrier for Ukrainian exports of critical agri-products, minerals and other raw materials to the EU from those regions.

One of the significant resemblances between the consequences of the Soviet blockade of Berlin and Russia’s illegal occupation of Ukraine is both pushed Europe into military consolidation under NATO. Within just months, previously neutral Finland and Sweden submitted NATO membership bids, which were unthinkable just a year prior. In both cases, Moscow’s aggressions prompted European armament and unification; not under a sovereign and unified European military force, but underneath a greater umbrella led by the United States.

Who is the primary beneficiary of European consolidation?

The US military-industrial complex is the massive winner of what Russia’s invasion of Ukraine brought for European security. US firms like Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, Northrop Grumman, and others are making billions from European states buying US arms and weapons like F-35s, Patriots, HIMARS, and more.

After the invasion, European orders for weapons spiked by over 50% in 2022–2024. The US supplied 64% of these arms. Pieter Wezeman, Senior Researcher with the SIPRI Arms Transfers Programme says “the European NATO states have almost 500 combat aircraft and many other weapons still on order from the US”.

As of 2025 more than ten European countries either fly or are buying F-35s. They are replacing their Typhoons, Gripens, Tornados, and F-16s with American made F-35. This may create technological, military, and political dependencies for the EU, which would be restraining “European strategic autonomy”.

Beyond the aforementioned disadvantages, the chances are that the US F-35s may function as tools of strategic control of the EU via “interoperability”. All F-35 user countries will have to rely on common software updates from the US. The mission data packages are going to be centralized, which means Washington can influence what a country can do with their planes, especially in war-like situations. Aside from these, logistics, training and engagement doctrines are precisely designed to serve interoperability.

EU’s Strategic Autonomy:

The EU is among the world’s richest regions in terms of Human Development and Innovation (HDI), as well as civilizational quality of life. However, as a multinational socioeconomic union, rather than a centralized political or military power, sustaining high living standards depends on stability of the flow of vital resources and supply-chains, including fossil fuels, critical raw materials(CRMs), rare earth minerals (REMs), and agricultural commodities.

In an increasingly competitive global order, where China, Russia and the US are clearly racing for global dominance in trade, tech, and resource control, the EU’s survival relies heavily on its capacity to secure strategic inputs it needs in the decades to come, and develop sovereign supply-chains.

The absence of sovereign and unified military force capable of projecting hard power or securing the EU’s critical resource corridors without relying on NATO is a foundational vulnerability addressed also in the EU’s 2016 Global Strategy report. This restricts the Union’s secure access to critical global resources beyond the continent and defend supply routes autonomously, especially in regions like MENA, the Arctic, and key maritime chokepoints.

Although Russia and the US are rivals in many areas, one of their aligned strategic interests is in the prevention of the EU from establishing a unified European military force, with which Europe’s dependencies on both powers could come to an end. Whether through diplomatic signaling, or backdoor agreements, both US and Russia benefit from a militarily consolidated EU; the US through NATO dominance, and Russia through playing the role of constant common enemy that threatens EU’s security, which often involves in large scale land grabs in EU’s much-needed alternative resource deposits like Syria, Ukraine, Libya, and South Caucasus.

For this reason, the EU’s path to “Strategic Autonomy” needs to be rooted not only in regulatory and soft power but in building economic, industrial and defense sovereignty.

“If Europe doesn’t decide to be a power, it will become a playground for others.” –- Emmanuel Macron, 2023

Regionalism For Greater Europe: European Security and Ukraine’s Strategic Role

Although some believe the world is de-globalizing and fragmenting, there are actually signs that globalization is still valid, but merely in a transitional period before setting the ground as new global order. This transitional period we are currently in can be referred to as “regionalism”, which in broader aspect -as political scientist Matthias Scantamburlo observed in a recent abstract presented at Universidad de Deusto- may be regarded as “loose federations or confederations”, serving functional integration, rather than ideology.

The fact of the matter is, the EU is adapting quickly to what regionalism offers in this post-COVID world: taking steps to access areas within the ‘Greater Europe’ region where strategic inputs like Critical Raw Materials (CRMs) and Rare Earth Minerals (REMs) are located. The EU acknowledges that strengthening the already-established political and security links with neighboring regions like Middle East (Syria), Caucasus (Azerbaijan), and Eastern Europe (particularly Ukraine and Moldova) is crucial for the Union’s economic and defense security.

Without a doubt Europe’s core interest lies in identifying optimized integration levels for one or more of these regions to make them part of the Greater Europe. This would not only secure Europe’s stable access to strategic resources, but help fend off rival global powers seeking to dominate the very supply chains Europe depends on, and profit from selling those resources back to the Union.

EUROPE'S EASTERN KEYSTONE: UKRAINE

Ukraine is now emerging as the cornerstone of Europe’s survival strategy in this century. Its fertile soils, mineral wealth, and nuclear capacity are indispensable to the EU’s energy, food, and resource sovereignty. Besides strategies concerning the security of supply chains, the war also reshaped Europe’s demographics. Ukrainian migration brought in younger and more dynamic labor force into the EU, helping to some extent to offset EUs aging population.

Following sections explore Ukraine’s strategic value in detail: its energy importance as a nuclear and grid partner, mineral importance as a source of critical raw materials (CRMs), and agricultural importance as the breadbasket of Europe. Ukraine is not simply another neighbor, but the eastern cornerstone of Europe’s strategic autonomy.

1) ENERGY IMPORTANCE:

Before the war in Ukraine, much of Europe had been in transition to nuclear power under The European Green Deal. Several member states decommissioned reactors, while many others pledged full phase-outs. Even the US under Democratic administrations aligned with this deal in transatlantic climate forums.

The war in Ukraine, however, changed this perception. Ukraine’s CRM and REM supply necessary for green energy (wind, solar, EV batteries) technology came under great risk. While even a full Ukrainian EU membership would not mean a guaranteed European access to these resources, Russia’s advances in key areas and the US signing mineral deals with Kyiv have significantly reduced the share of CRM/REM supply the EU had hoped to secure.

The Trump–Putin summit in Alaska has a bit weakened the EU’s position in Ukraine’s de facto partition. While Kyiv being excluded from the talks, Washington and Moscow likely discussed issues regarding CRM/REM compensations that Russia may consider accepting in exchange for giving up some of the lands it occupies in Ukraine, likely around Zaporizhzhia, a very strategic oblast home to fertile lands, vital nuclear plants and critical minerals.

In addition to the challenges the EU has been facing with raw material supply that the green energy sector requires, Moscow’s strategy to weaponize energy against Brussels played a role in shifting the Union’s approach to energy autonomy. Brussels quickly came to realization that some significant adjustments had to be made in the European Green Deal to include nuclear power, at least for as long as instability in Ukraine persists. But because the reactivation of many decommissioned reactors would be costly and slow, the EU turned to Ukraine’s nuclear power plants, which were already operational, and modern enough to be integrated quickly.

Ukraine’s integration to European grid system:

Ukraine’s grid was part of the Russian-Belarus system, aka IPS/UPS system, before March 2022, and was controlled from Moscow, just like the Baltic states, which were integrated into the European grid as recently as February 2025. All necessary technical and infrastructural support that these states needed had been provided by Belarus and Russia. Moscow used this for years as a strategic control mechanism to maintain leverage over these countries.

The integration of Ukraine’s power grid into that of Continental Europe through synchronization with the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity (ENTSO-E), was actually scheduled for 2024. However, due to growing risks posed by Russia’s invasion to the security of energy infrastructure, the synchronization had to be rescheduled and was eventually completed two years earlier, in March 2022. This was a strategic step forward for the EU because Europe has now secured a significant portion of Ukraine’s energy supply and export capacity from crucial Nuclear Power Plants (NPPs).

Ukraine’s Nuclear Power Plants (NPPs) and Their Role in Powering the EU Grid:

Ukraine is heavily reliant on nuclear energy. According to the International Energy Agency, prior to Russia’s invasion, Ukraine’s nuclear power plants generated 50% of the country’s electricity, followed by coal (23%) and gas (9%). There are currently 4 NPPs in Ukraine: Zaporizhzhia, Rivne, South Ukraine and Khmelnytskyi. Rivne, South Ukraine and Khmelnytskyi NPPs are all fully operational and are controlled by Kyiv government. These three NPPs are also currently supplying European grid, particularly for countries like Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, Moldova and Poland.

Zaporizhzhia NPP and its strategic importance:

Although the other three NPPs are generating excess power to feed in the European grid now, they may not be enough for the needs of post-war Ukraine. Zaporizhzhia NPP is the largest in Europe with six reactors generating ~6 GW (20% of Ukraine’s electricity before the war) when it was in full capacity. Before its seizure by invading Russian forces in 2022, who later shut it down, Zaporizhzhia alone was generating more than 2.5 times Estonia’s national power production capacity; roughly 2.3 GW. It could power multiple small EU countries just by itself.

Western projects in Ukraine depend on stable and high capacity electricity because they are mostly in energy intensive sectors like mining or agricultural production. That is why for Brussels Zaporizhzhia NPP is a strategically important energy source that might be both stabilizing Ukraine’s grid and utilizing it for the EU’s future energy demands to sustain strategic interests of the western partners regarding operations inside Ukrainian territory.

From a strategic standpoint, Russia’s seizure of the plant can be seen as preemptive energy denial strategy. By shutting down the largest NPP in Ukraine Moscow managed to disrupt Kyiv’s potential energy supply lines, and in turn, limit Europe’s operational footprint in the regions controlled by Zelensky. This gave Russia a strategic leverage to pressure Brussels toward concessions, as well as making it clear that the EU’s dependence on centralized, vulnerable energy sources outside its borders carries geopolitical risks.

As a result, Brussels has begun rethinking its post-war energy strategy not only through ENTSO-E integration, but by introducing decentralized nuclear solutions like Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). These reactors are faster to build and deploy, without dealing much of the usual constrains and logistical risks the traditional plants have. SMRs can reinforce Europe’s energy independence in the East, and help sustain energy intensive operations in Ukraine’s mines and agricultural centers, both of which are crucial to the EU’s future supply chains.

2) MINERAL IMPORTANCE:

In a post-COVID world, where deep political fragmentations are forcing political and military consolidations around larger powers in the same region, the EU neighboring a global power like Russia, is facing the dilemma of being “the world’s industrial giant with no resource sovereignty”. With rising global competition over critical raw materials (CRMs) and rare earth minerals (REMs), Brussels is aware that access to strategic inputs is as vital as innovation or capital. In this sense, Ukraine becomes one of the EU’s last remaining chance to stay in the global race for supply-chain security, and gain resource sovereignty to a certain extent.

Ukraine’s Mineral Wealth:

Recognizing this, the EU took a serious step forward and laid out its CRM Action Plan in 2020. This plan revealed two strategic goals aligned with Brussels’ broader plans to get Ukraine closer to the Union: first, to “strengthen domestic sourcing of raw materials”; second, to “diversify sourcing from third countries”. Obviously, a full Ukrainian membership would fulfill both objectives naturally. In line with the action plan, the EU also signed Mineral Cooperation Agreement with Ukraine in 2021, formalizing its intention to integrate Ukraine into supply chains. The agreement aims to promote joint projects in CRM and REM mining, battery production, and hydrogen technologies.

The latest study on Critical Raw Materials for the EU in 2023 identified a list of 34 CRMs as “high economic importance” for the security of the Union’s industrial value chains. According to another report published by the Ministry of Economy of Ukraine in 2024, Ukraine hosts 22 out of the EU’s list of 34 CRMs. This same report also notes that the EU aims to incorporate Ukraine’s raw materials into its battery value chains, while US considers a strategic partnership with titanium production.

EU’s Strategic Mineral Vulnerability:

It is clear that Brussels sees Ukraine not just as a neighbor, but as a “strategic resource base”, critical for reducing Europe’s mineral dependencies on adversarial states like Russia and China. While part of the Kremlin’s destabilization efforts in Ukraine aims at controlling the country’s mineral supply, on which the EU is heavily dependent, China’s dominance in processing extracted minerals adds up on Europe’s existing strategic vulnerability.

Scotland-based credible data analytics and research firm Wood Mackenzie reports that China accounts for 85% of global REM production through its six state-owned enterprises, giving Beijing enormous control over both the supply and pricing of REMs worldwide. Another report by Polish Economic Institute states 98% of the REMs imported by the EU come from China. The president of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen pointed out the exact same REM supply dependency rate on Chinese REM supply, while also alluding to Senkaku dispute to highlight how China becomes unhesitant in using such dependencies as bargaining chips or to gain concessions.

Many reports from various different reputable sources state that global demand for REMs is expected to grow by sevenfold by the end of the next decade. Considering Europe’s current rate of reliance on Chinese REM supply will also likely continue to grow for at least a while, there is a significant risk for the EU ending up like Japan during a potentially serious foreign policy dispute with China sometime in the future. Nevertheless, there are already news reports about how Beijing has pressured European firms operating in China to transfer tech to local firms, a practice that has been widespread, and ongoing for more than six years.

Ukraine’s Lithium Deposits and Global Players:

Lithium is an ultralight metal primarily used in lithium-ion batteries, which power electric vehicles (EVs) and various devices such as smartphones, laptops, tablets, power tools, medical equipments, and home solar systems. Therefore the metal has a rapidly growing global demand. In May 2024, Conflict and Environmental Observatory published a report on Ukraine’s minerals mentioned lithium among beryllium, zirconium, scandium and vanadium, as a CRM deposit that is specifically in great demand on the European market, with a strong potential for large scale development. Significant portion of the EU’s mineral vulnerability stems from its limited access to strategic lithium reserves. This fact is also underscored by Fastmarkets, who projects that by 2032, Europe will represent 25% of lithium demand, but contribute only 4% of global lithium supply.

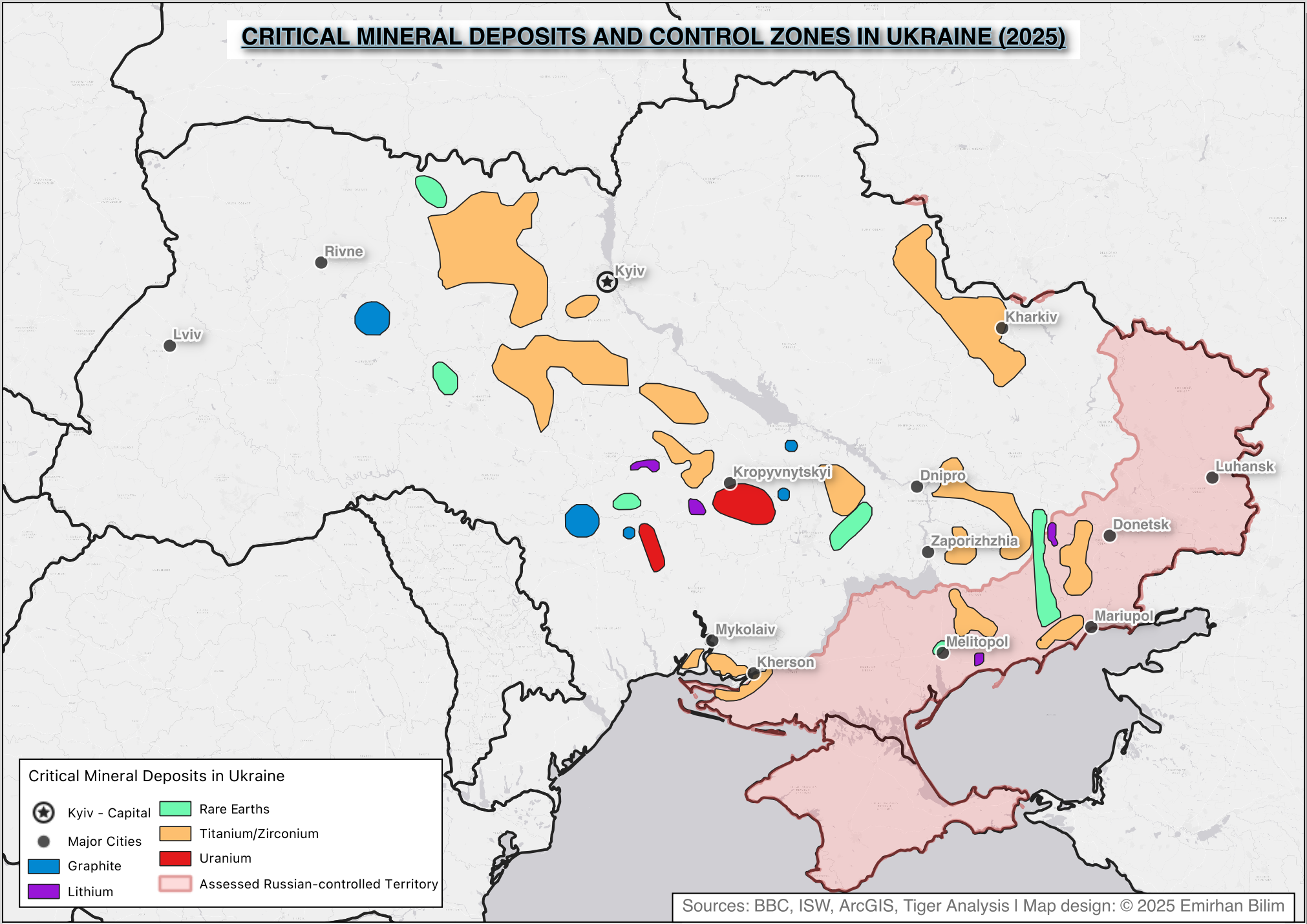

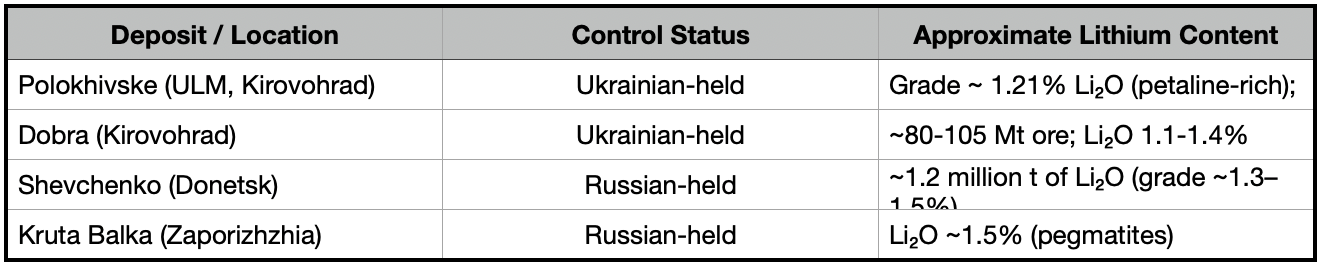

Ukraine’s lithium reserves are located primarily in central and eastern regions (see figure 2). In the central region of Kirovohrad, two deposits are under Ukrainian control; Polokhivske and Dobra. However, the key ones like Shevchenko in Donetsk, and Kruta Balka in Zaporizhzhia regions are now under Russian occupation since early 2025. Shevchenko site is considered as the most valuable and the largest confirmed lithium deposit in Ukraine. It is also among one of the biggest lithium deposits in Europe along with the ones in Serbia and Portugal.

Another noteworthy development regarding the importance of Ukraine’s strategic mineral deposits for global powers is, China’s attempt to seriously involve in direct extraction of lithium from the aforementioned two lithium sites. In November 2021, just prior to the war, Chinese state-owned enterprise Chengxin Lithium Group made bids for obtaining licenses at both Polokhivske and Shevchenko to seek a foothold in Ukraine’s mineral reserves. But the war disrupted review processes and Shevchenko fell into the war zone, then eventually Russian control. Although Polokhivske is still under Ukrainian control, Kyiv’s alignment with the EU automatically prioritized European interests, and killed the foreign bids on strategic assets from China and Australia.

Yet, in a broader picture China’s overturned bids in Ukraine did little to harm its overall interests. Russia’s control over key mineral-rich oblasts is still denying the EU’s access to alternative “non-China supply”, which Brussels had long been hoping to tap into to diversify away from Beijing. Thus, the interests of global powers once again aligned in Ukraine.

3) AGRICULTURAL IMPORTANCE:

Ukraine’s Fertile Farmlands and EU’s Food Security:

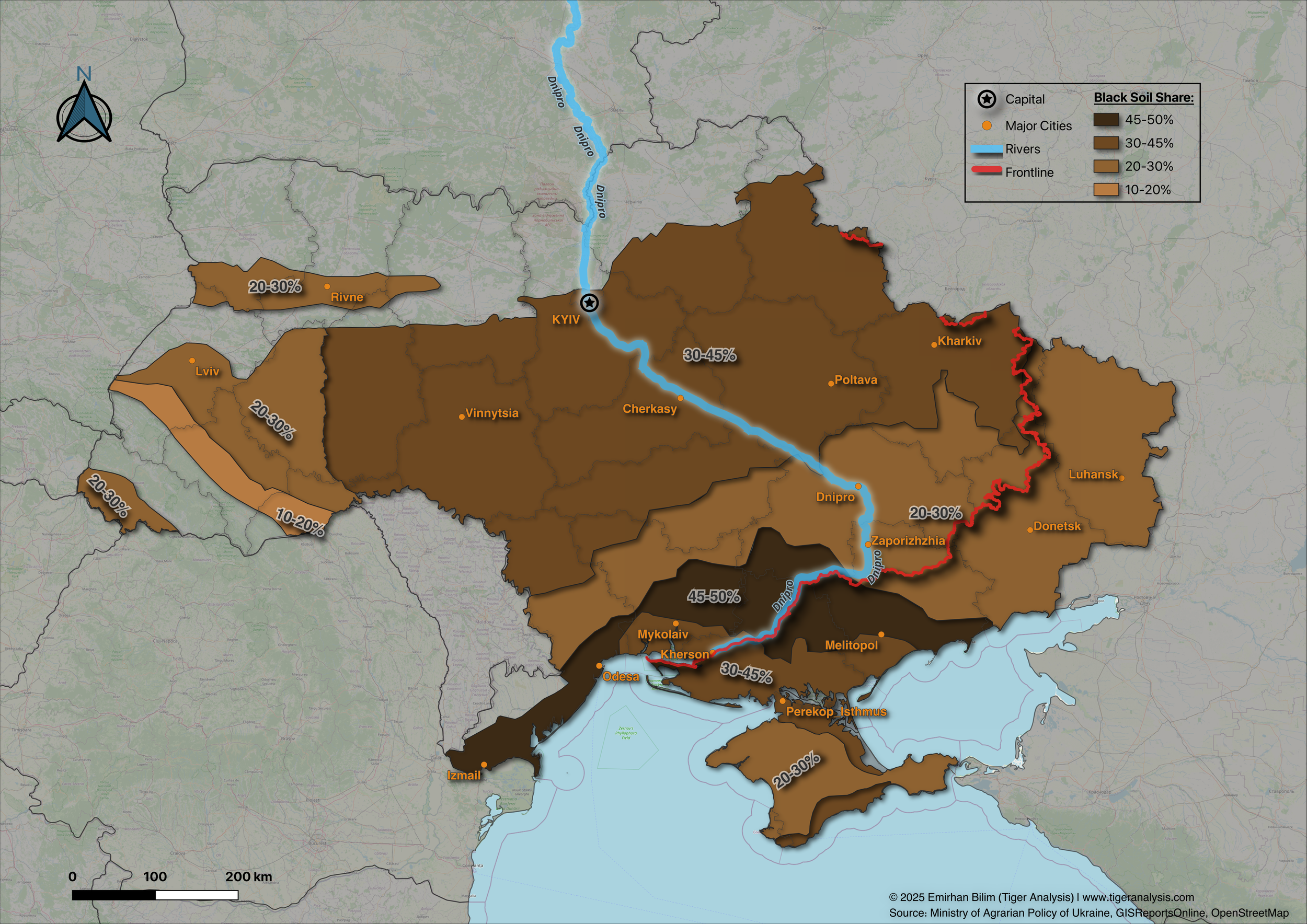

Ukraine is known as the breadbasket of Europe, and home to 33 million hectares of arable land, nearly 70% of its total land area. The central and southern regions of the country contain large concentrations of a soil type rich in humus, phosphorus and ammonia, known as Chernozem (Black Soil), which is widely regarded as the most fertile soil on Earth. Besides Chernozem, Ukraine’s vast river network supports excellent agricultural conditions.

In 2024, the EU imported over €15 billion farm products from Ukraine, including sunflower oil, soybean oil, and maize. This accounted for almost 36% of total agricultural exports of the country, making Ukraine an essential supplier to the EU’s livestock sector.

Kyiv’s EU membership would definitely help reduce the union’s strategic dependency for agri-products, like soybean. Studies suggest that with Ukraine’s membership, the EU would surpass Russian wheat production by producing a third of global supply. Russian occupied Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson are actually parts of the “fertile corridor” in Ukraine, with arable lands that are up to 45-50% rich in black soil, making up a good portion of total black soil deposits of Ukraine.

Logistics problem:

When Kyiv signed EUAA, which also included “Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area” (DCFTA), the EU has finally achieved partial liberalization of Ukrainian agri-products, and their exports. However, Russia’s blockade of Black Sea ports disrupted European plans to establish a seamless crop supply-chain, which is an indispensable component of EU’s “strategic autonomy”. As much as export security for Ukrainian agri-products, accessing the Black Sea has also critical logistical importance for the EU. The Russian occupation of Crimea locked in the Sea of Azov, making the shorelines of the oblasts rich in black soil like Kherson, Zaporizhzhia and Donetsk inaccessible. Figure 2 above shows the distribution of critical minerals close to Azov shores, providing a broader angle as to why accessing ports like Mariupol was vital for the EU.

Aside from the EU’s denial of access to those ports, Moscow also maintains a strong naval presence in Crimea, with which it is threatening the EU’s existing access to Odesa port, an oblast also falls in the fertile corridor. Despite Ukraine’s military push-backs in the Black Sea to keep the Russian navy at check, Moscow uses hard power at sea to leverage its position against the EU’s demands anytime it considers necessary.

Another serious challenge the union faces today is its stakes in Ukraine is shrinking as non-EU competitors are expanding their footprints. The EU commission, in response to a Belgian parliament member’s written question in 2024 on US and Saudi corporations investing heavily in Ukraine’s arable lands, realizes the importance of Ukraine maintaining and improving the Black Sea ports to continue being a crucial source for the EU’s strategic food-supply dependence.

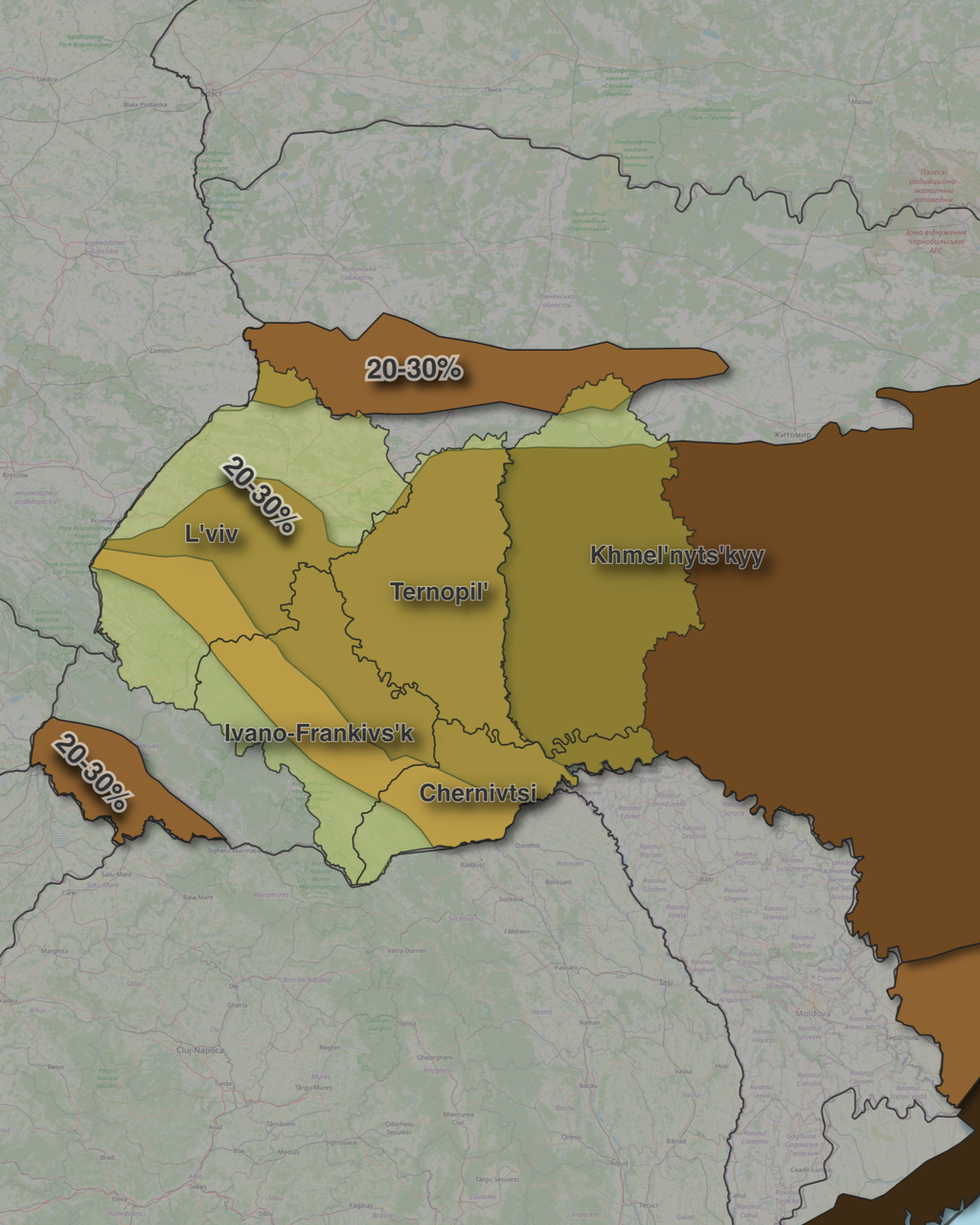

The parliament member’s concerns stated in the enquiry however, aren’t unfounded. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s (KSA) involvement in Ukraine is more significant than most people would think. The United Farmers Holding Company of KSA controls 195,000 ha of Ukrainian farmland through a subsidiary called Continental Farmers, which is operating in Western Ukraine, in oblasts like Ternopil, Lviv, Khmelnytskyi, Chernivtsi and Ivano-Frankivsk.

Figure 5 above highlights the five western oblasts where the KSA agricultural operations are currently active. The concentration of chernozem in this region is among the most fertile in western corridor, with average black-soil shares ranging from 10 to 45% (Khmelnytskyi sits in 30-45% zone) of arable lands. There are handful of EU member states with farmlands in much lesser quality and/or having very limited arable lands, such as Finland, Sweden, and Austria. Considering an important portion of the fertile corridor is now under Russian blockade in the southeast, the rest of Ukraine’s arable lands become vital for the food security of the EU.

The involvement of non-EU members in Ukraine, like that of the KSA, is further complicating things for Europe, as the unions strategic agricultural planning faces a greater risk of diminishing output due to less shares from Ukraine’s fertile corridor. This new agricultural reality is also one the most significant factors pushing the EU toward a military consolidation under NATO umbrella, with member states that have poor arable lands, like Finland(~7% arable share) and Sweden(6.5% arable share), having rushed to submit NATO bids accepted as recent as last year. Such EU members would have been highly unlikely to access Ukraine’s rich farmlands had they not joined NATO whilst Russia is threatening and the US is prioritizing NATO members.

KEY TAKEAWAYS AND SUMMARY:

From Yalta to Crimea, Europe’s destiny has always been to confront Russia. Even when things should look differently, with Moscow building pipelines and feeding into European grid systems and industries, the term “dependency” was always there lurking behind shadows to trigger tensions at any levels. Be it the EU struggling with Moscow’s never-ending demands for keeping the taps open without problems, or with China forcing tech transfers as prerequisite for doing business, or even with the US just having realized Russia gaining market share, it all comes straight down to the control of the EU’s vast demands for resources located away from the continent, such as minerals, energy and agricultural output.

So the name of the game is, who controls what the EU needs?

How Global Powers Keep Europe Dependent?

Although dependencies like uranium, or REM processing are also a significant risk factor even for the most powerful country on the planet, the US, all global powers, including Russia and China, are happy to see Europe being no more than a rich, disarmed customer, who has no alternative but to shop from their stores, “even if they are not the owners of those stores”. There are clear indications that sometimes these powers benefit together from restricting Europe’s access to the resources. They are aiming to enslave European demand for resources by controlling supply-chains, and the regions the EU may tap into independently.

One of the most recent examples of this was seen in Syria, a country where European interests have been solid. Russia-backed groups shared Syria with the US proxies for years by the Euphrates river serving as natural boundary in between. They did not allow any other major or local actors other than Iran to join in for some while. The Europeans had to go through all of the three separately, and made complex deals to secure logistics lines from the east of the river to the Mediterranean shores.

Russian Wagner’s involvements across Africa, especially in places where some EU members’ interests were historic, like Central African Republic (CAR) and Niger, are also noteworthy in this respect. Russian paramilitaries replaced the French in CAR and began controlling mines with exclusive mining rights granted by the government.

China also watches closely how European interests are shaping with obvious concerns that they may shift away from China to alternative regions, thus makes moves to secure the resources before Europe takes serious steps in that manner. Some of the few examples for such Chinese attempts are China’s involvements in Ukraine and Greenland. Before the war, Beijing invested in a highly strategic region of Ukraine, Mariupol, where Chernozem is the richest, as well as in Ukraine’s aviation (Motor Sich) sector.

Another worthy of mention attempt by China to grab a piece of European resources before Brussels could develop any serious extraction projects, has taken place on the EU soils, Greenland. China’s Shenghe Resources is the largest shareholder in Greenland Minerals (now Energy Transition Minerals), which owns Kvanefjeld in the Kaunnersiut mountain area, where one of the world’s largest REM deposits is located at. This is a clear sign from a global power, who is producing 60 percent of the world’s REMs, and processing nearly 90 percent, is trying to restrict Europe from even potentially turning back to its own resources.

Beijing is obviously aiming for the same thing as Moscow; trying to control what Brussels needs to sell it back to the union, or using it for concessions like obtaining strategic inputs such as tech transfers. No matter what the EU demand is held back for by the three global powers, their treatment is not any short of mob bosses extorting favors from rich businessmen (in this case money and innovation), in exchange for security (NATO), and access to the usurped valuables (critical resources).

The EU’s Struggle for Strategic Sovereignty:

The EU has been trying to break the dependencies the three global powers shackled it with. On the other hand, as a multinational union, the EU is knitted with institutional bureaucracy to the core. Although this indispensable norm-setting part of the union’s political structure is a great contributor to the human civilization in many aspects, it also functions as a serious obstacle when taking on aforementioned challenges.

Realistically speaking, we are in a post-liberal world where Russia steals resource-rich lands at gunpoint; China weaponizes debt to grab CRMs in Africa and MENA; and the US uses Russian aggression as reason to sell weapons and LNG while never letting the EU forming its own unified army. What Europe is left with is being the world’s industrial giant without resource sovereignty. Frankly, securing resources solely by the use of diplomacy does not seem possible anymore, especially since Trump’s first term. So, the future of having sustainable industries in Europe without being a market colony of global powers is one the biggest challenges for Brussels to tackle down.

The Security Action For Europe (SAFE) program may sound at first as creation of an independent European army, but it is actually a funding plan to build Europe’s “military-industry complex”, which may decrease defense dependencies in mid to long term, although definitely not a step taken for the formation of an independent army.

Europe’s Path Forward:

In its pursuit of strategic sovereignty the EU needs a certain degree of hard power unification, which may even be coupled with a highly-integrated, centralized body of intelligence unit. However, with a declining population, migration weaponized, and the US forcing consolidation under NATO, the EU’s chances to build a unified military to have the necessary means in safeguarding access to strategic resources seems low, at least for a while.

If Brussels manages to strategize a blend of some soft-power with a limited but efficient hard-power, without the restrains of veto-dodging political maneuvers, it could reverse the balance in the next decade. Because a potential change in the Article 4 TEU would require consent of all member states, including the ones that are close to Moscow, the formation of a ministerial level governing body acting like a defense ministry of the entire union, may not be possible. Regardless of the political complexities, it would not make Washington happy either.

Therefore, a solution might be in forming an “enhanced cooperation treaty” for select number of member states, who could give limited powers to a shared defense authority that binds only themselves. This authority, unlike EI2 or PESCO, could form a common multinational private military contractor firm with a unified command-chain that aims to protect the mutual interests of those members wherever necessary.

Crux of the matter is, Ukraine is one of the last cards on the table for Brussels. Like Russia, the EU also has the home advantage there. All it takes is a dedicated strategic approach that is directly confronting the hard truths and structural challenges the union faces in this ongoing geopolitical shift.

Written by Emirhan Bilim | October, 2025

© 2025 Emirhan Bilim. All rights reserved.

This article is the intellectual property of Tiger Analysis (www.tigeranalysis.com). No part of this content may be reproduced, copied, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including quoting, without prior written permission from the author. Unauthorized uses will be treated as a violation of international copyright law.

Ukraine’s Nuclear Power Plants and Their ENTSO-E Integration:

Figure 1: Ukraine’s Power Infrastructure and Grid: The map depicts Ukraine’s major nuclear power plants (NPPs), transmission corridors, and interconnection lines with the European ENTSO-E grid. Data derived from IAEA PRIS, Energoatom, ENTSO-E, Ukrenergo, OpenStreetMap, ISW/CTP.

Visualizations, and spatial adjustments in QGIS by Tiger Analysis (© 2025 Emirhan Bilim).

Figure 2: Ukraine’s Strategic Mineral Deposits. The map shows the distribution of key mineral and REM deposits across Ukraine, including areas under Russian occupation as of 2025.

Data compiled from USGS, Ukraine Geological Survey, and media sources.

Map interpretation and geospatial composition in QGIS by Tiger Analysis (© 2025 Emirhan Bilim).

Figure 4: Ukraine’s Black Soil (Chernozem) Concentration Within Total Arable Lands: The map illustrates the approximate share of chernozem within Ukraine’s total arable farmland area.

Data are derived from the Ministry of Agrarian Policy of Ukraine and GISReportsOnline.

Visualization and spatial adjustment in QGIS by Tiger Analysis (© 2025 Emirhan Bilim).

Figure 5: KSA Agricultural Operations in Western Ukraine: The layer shows five western oblasts; Lviv, Ternopil, Khmelnytskyi, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Chernivtsi, in which the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia owns farmlands as vast as 195,000 ha.

Data derived from Continental Farmers Group’s webpage

Visualization and spatial adjustment in QGIS by Tiger Analysis (© 2025 Emirhan Bilim)

Major Lithium Deposits in Ukraine: Control Status and Estimated Content as of August 2025

Figure 3 Major Lithium Deposits in Ukraine: Table shows Ukraine’s principal lithium-bearing deposits and their current control status as of 2025. The listed sites represent the country’s key hard-rock (pegmatite and petaline) resources, concentrated mainly in Kirovohrad, Donetsk, and Zaporizhzhia. Data taken from Ukrainian Geological Survey, and USGS.

Table formatted and annotated by Tiger Analysis (© 2025 Emirhan Bilim).